MULTI-TRACK RECORDING

The next step in my recording odyssey was to acquire a multi-track recorder. Instead of having to “bounce” tracks on a stereo, sound-on-sound recorder (see “John’s History of Recording: Part One”), I wanted to record at least four separate tracks either simultaneously or one at a time, process them separately, and ultimately mix them together while recording them on another tape recorder to create a master 2-track stereo recording. (See the Otari MX5050 at the end of this blog)

TEAC 3340S 4-Track Recorder

In 1977, I secured a loan from my parents to buy a multi-track tape deck, which I believe cost about $1,300 (or about $6,500 in today’s dollars).

It used 1/4” magnetic tape and ran at both 7.5 and 15 ips (inches per second). The tracks, like all tape machines, produced tape hiss in the recording process and the more tracks you had, the more tape hiss you got.

The machine also had “Simul-Sync,” which allowed me to monitor off the record head, making it possible to keep everything in sync when overdubbing. I spent many a happy hour recording and re-recording with that deck.

Here’s a piece called “Yellow Fire” that I recorded on the 3340S in 1978 or 1979:

The next stage of my recording quest involved getting a hold of an 8-track recorder. More tracks meant being able to record more instruments without having to “bounce.”

OTARI MX5050 8-TRACK REEL-TO-REEL TAPE MACHINE

In 1980, I got a job teaching recording skills to teenagers at a place called Somerville Media Action Project (SMAP) in Somerville, Massachusetts. Somehow, we were able to get access to an Otari 8-track recorder. This was a state-of-the-art machine that used 1/2” tape rather than 1/4” and had twice as many tracks as my 3340S.

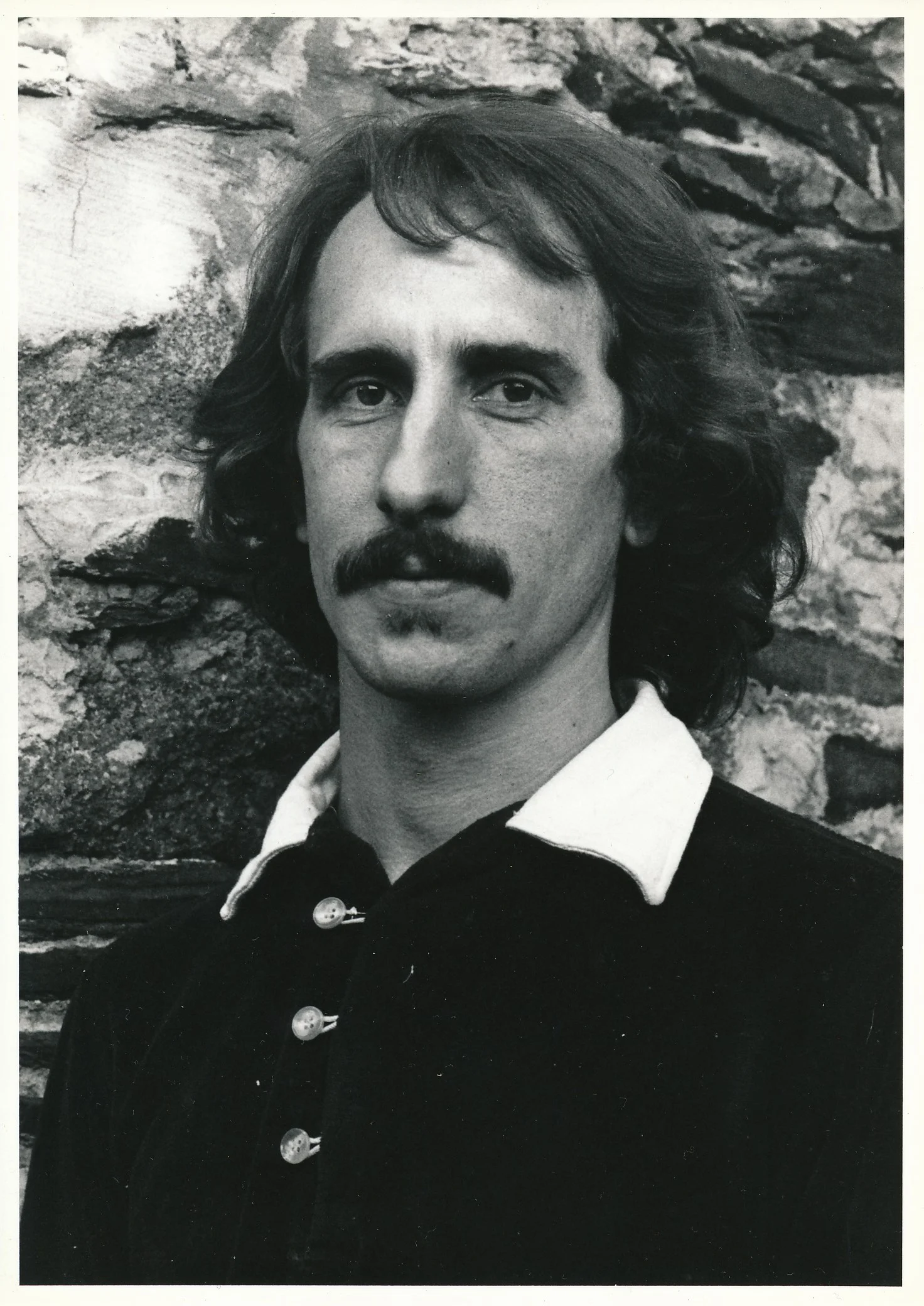

Below is a picture of the control room at SMAP and a couple of the recording engineers (that’s me on the left). The transport for the 8-track is next to my right arm; the electronics for it are behind my head. They were connected by a large cable that allowed the two parts to be separated.

I wrote and recorded the following song (“Morning Madness”) on the MX5050:

The gradual improvement of recording quality among the examples I’ve included here demonstrates evolving tape recording technology, including more tracks as well as the recording engineer’s evolving skills and experience.

Next up, 16 tracks!

Otari MTR 90 MKII - 2” 16 track tape machine

This is a picture of me mixing music at Silver Linings, Inc. in Boston, Massachusetts, where I worked as an audio engineer from 1984 to 1991. We offered “mix-to-pix” for visual media (slide-shows, videos and television) and we had two Otari 16-track decks.

You can see part of one of them at the right side of the picture. Just to the left of the machine is the roll-around remote controller for it. All functions of the deck were available from the remote.

It was a very well-made and great sounding tape recorder and the 2” tape came on heavy reels that could run at 15 or 30 ips. We edited the tape with razor blades!

Here’s a composition of mine called “Bass Desire” that was recorded on that Otari 16-track:

All the multi-track recorders than I have been discussing here were the first step in the recording process.

Once I had completed the basic recording of tracks, those tracks would be mixed together through a multi-channel mixer and recorded on a 2-track recorder. That 2-stereo mix would then be transferred to CD, cassette, or other media for listening.

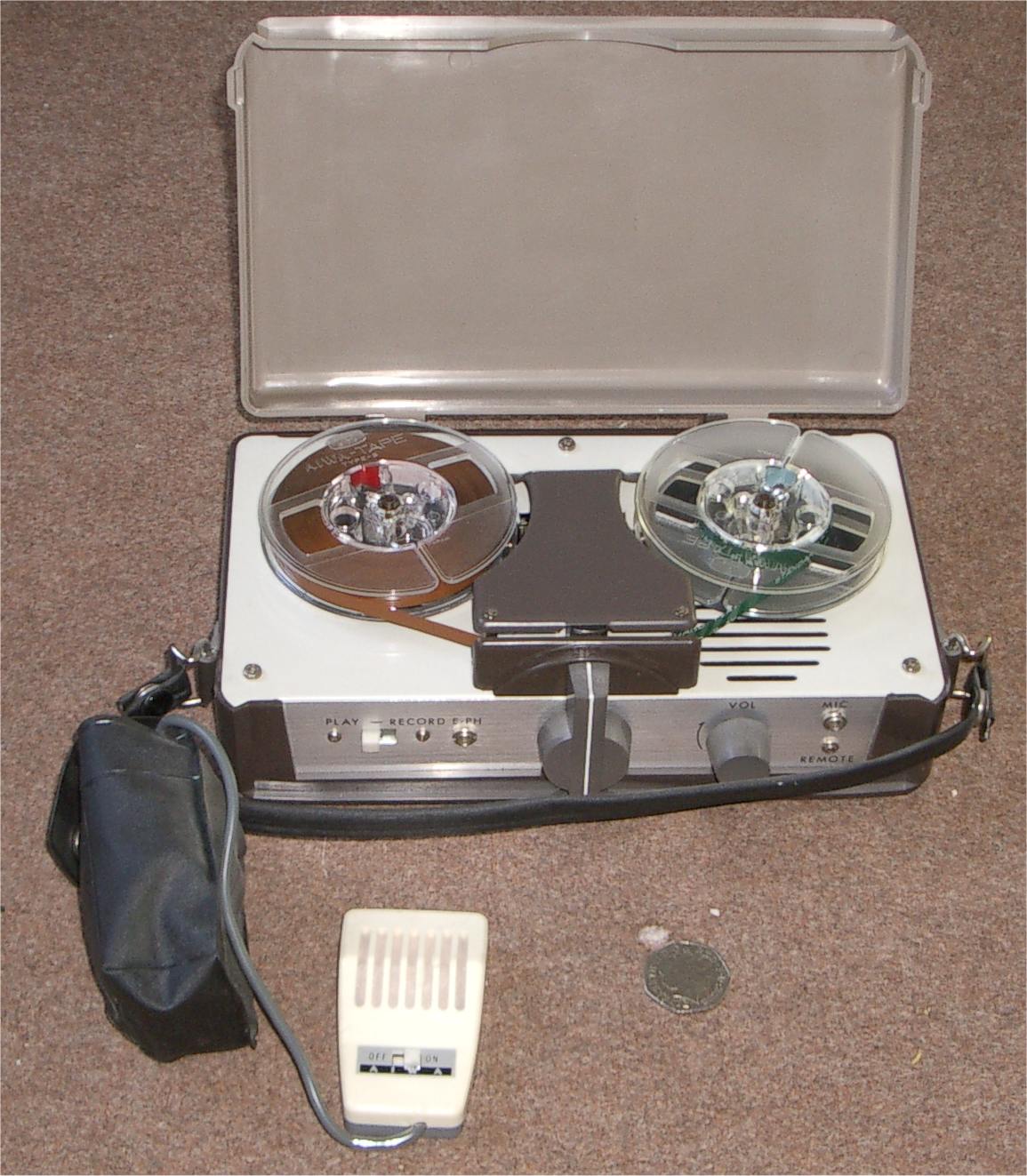

Here’s a picture of the deck I used most of the time for that purpose, the Otari MX505 2-track tape recorder.

In 1992, I stopped working with tape recorders and began to record exclusively via digital, first with Digidesign Soundtools and then with Digital Performer software on Apple Macintosh computers—but for that part of the story, see the upcoming “John’s History of Recording, Part Three!”